Last Wednesday, President Donald Trump announced his “Liberation Day” tariffs, which elicited quite a response from the media, lawmakers, and economists alike. (One week later, he announced a 90-day pause on his plan due to the backlash.) Trump is far from the first president to divide the American people over what the Founders often called “duties.” Prior to the passage of the Sixteenth Amendment, which granted Congress the power to “lay and collect taxes on incomes,” the federal government’s primary source of income came from tariffs, meaning they played an integral role in early political debates. In this piece, we will examine how various presidents interacted with tariffs between 1789 and 1913, when the Sixteenth Amendment was adopted.

(Note: not every president from that period is included on this list.)

1789-1833

George Washington signed the nation’s first tariff act on July 4, 1789, 68 days into his presidency. It was the first major law passed by Congress. Introduced by then-Congressman and future President James Madison, the legislation, which implemented a 5% baseline tariff on most imported goods, was deemed “necessary for the support of government, for the discharge of the debts of the United States, and the encouragement and protection of manufactures . . . .”

As expressed in Federalist 12, Alexander Hamilton, Washington’s Secretary of the Treasury, favored tariffs on “ardent spirits … to furnish a considerable revenue” and “diminish the consumption of it.” While early American tariffs penalized imported wines, Thomas Jefferson blasted Hamilton’s plan as “a tax on the health of our citizens.” In his view, decreasing wine consumption condemned “all the midling & lower conditions of society to the poison of whisky, which is destroying them by wholesale, and ruining their families.” Overall, Jefferson opposed tariffs, partially because he did not want the federal government to become rich and powerful.

John Quincy Adams played a key role in implementing one of the most controversial tariffs in American history. The Tariff of 1828, which set the highest tariff rates the nation had ever seen, was generally supported by Northern states but faced vehement opposition in the South. Southern critics, outraged by its economic impact, famously branded it the “Tariff of Abominations.” They claimed it favored the North’s factories over the South’s agricultural economy.

The tariff helped Andrew Jackson triumph over Adams in the 1828 presidential election; it also prompted John C. Calhoun, vice president under Adams and Jackson, to anonymously write a widely-circulated paper promoting nullification, the controversial argument that the states could invalidate unfavored federal laws. Southern voters assumed that Jackson, a Southern cotton planter, would oppose the tariff. To their disappointment, the president allowed it to continue, exacerbating what became known as the Nullification Crisis. A subsequent measure, the Tariff Act of 1832, although slightly reducing rates, did not help the situation.

Later that year, South Carolina, Calhoun’s home state, passed the Ordinance of Nullification, renouncing tariffs as “null, void, and no law.” Many feared the state would secede. As tensions between South Carolina and the federal government escalated, Senators Henry Clay and Calhoun, who had resigned from the White House and been elected to Congress the previous year, negotiated the Tariff (or Compromise) of 1833, which appeased both sides.

1842-1865

This tariff was eventually replaced by the Tariff of 1842, also known as the Black Tariff, reluctantly passed by John Tyler and later replaced by James Polk’s Walker Tariff. The Walker Tariff was then amended by the Tariff of 1857, which Franklin Pierce signed into law the day before James Buchanan became president, slashing rates to the lowest they had been in decades. Buchanan declared his support for the modified tariff in his inaugural address the following day. Unfortunately, when the Panic of 1857 struck months later, public sentiment on the tariff soured.

Buchanan’s more popular successor, Abraham Lincoln, was an outspoken proponent of tariffs. “In the days of Henry Clay I was a Henry Clay-tariff-man; and my views have undergone no material change upon that subject,” Lincoln wrote. However, as president during the Civil War, Lincoln navigated a tariff dispute unlike any his hero Clay had encountered.

Two days before Lincoln was inaugurated, even as Southern states seceded in protest of his election, Buchanan signed the Tariff Act of 1861, also known as the Morrill Tariff Act, into law. Introduced by Vermont Senator Justin S. Morrill, this heavy-handed tax on imported goods disproportionately threatened the Southern economy. Moreover, it had the unfortunate effect of alienating Britain, which was strongly pro-free trade at the time, against the Union — a fact that the Confederacy happily exploited. As Richard Cobden, a member of Parliament, informed U.S. Senator Charles Sumner, “There are two subjects on which [the English] are unanimous and fanatical — personal freedom and Free Trade.” Many of Cobden’s contemporaries, including Charles Dickens, misinterpreted the tariff as the inciting incident that, in Dickens’ words, “severed the last threads which bound the North and South together.”

Revisionist historians have frequently made the same mistake, overstating the Morrill Tariff Act as a primary cause behind the Civil War. In reality, seven of the eventual 11 Confederate states had already seceded by the time Buchanan signed the tariff. In fact, their absences from Congress enabled the bill to pass. However, the Morrill Tariff Act may have played a crucial role in the passage of the Emancipation Proclamation, which Lincoln issued, at least in part, to woo the strongly anti-slavery Brits back to his side.

1865-1913

The Democrats’ weakened post-war influence freed Republicans to pursue a more protectionist tariff policy. Additionally, the nation’s debt had grown from roughly $65 million before the war to $2.6 billion after the war, making higher tariffs a logical response to paying off what Lincoln rightly called an “unprecedented” national debt.

“As soon as the revenue can be dispensed with, all duty should be removed from coffee, tea and other articles of universal use not produced by ourselves,” said Ulysses S. Grant in his Second Annual Message to Congress. “The necessities of the country compel us to collect revenue from our imports. An army of assessors and collectors is not a pleasant sight to the citizen, but that of a tariff for revenue is necessary. Such a tariff, so far as it acts as an encouragement to home production, affords employment to labor at living wages . . . .”

Despite Grant’s plans to eventually phase out the program, tariff rates continued to climb during this period, prompting Chester A. Arthur, a Republican, to question whether big businessmen who produced domestically had influenced lawmakers to hike the rates. On May 15, 1882, Arthur created the U.S. Tariff Commission to investigate the matter and propose tariff reductions. The commission recommended a 20-25 percent rollback, which the president began lobbying for in Congress. The legislature, despite having a Republican majority in the Senate, rejected the president’s plan. In the end, they settled for the Tariff of 1883, or the Mongrel Tariff, which modestly cut rates by less than 5 percent.

Breaking with his party over the tariff issue, Arthur, who also suffered from poor health, cemented Republicans’ growing distrust of their leader, leading them to replace him with the scandal-ridden James G. Blaine in the 1884 presidential election. After a less than cordial campaign, the contest ended with Grover Cleveland besting Blaine to become the first Democrat to serve as president since Andrew Johnson and the first elected to the position since Buchanan.

The first and only president before Trump to serve two nonconsecutive terms, Cleveland acknowledged that, in his view, tariffs had become too high. However, his time in office was interrupted by Benjamin Harrison, who signed the McKinley Tariff of 1890. Sponsored by then-Representative and future president William McKinley, this act raised tariffs to nearly 50 percent, earning McKinley the nickname the “Napoleon of Protection.”

Returning to office in 1893, Cleveland fired back with the Wilson-Gorman tariff bill, which sought, once again, to lower rates. It also implemented an income tax to compensate for lost government revenue. Unfortunately for the president, the bill was marred (opponents amended it over 600 times) and less effective than he had hoped.

Indicating a steady back-and-forth in public sentiment regarding tariffs, McKinley, of tariff fame, captured the presidency following Cleveland’s second term. Cementing his legacy as the king of tariffs, the new president swiftly signed the Dingley Tariff, “the highest protective tariff in American history to that time.” However, after McKinley was assassinated in 1901, his successor took a new approach; Theodore Roosevelt largely sought to avoid the issue. Although he indicated that he preferred an income tax over tariffs, he did little to push the issue.

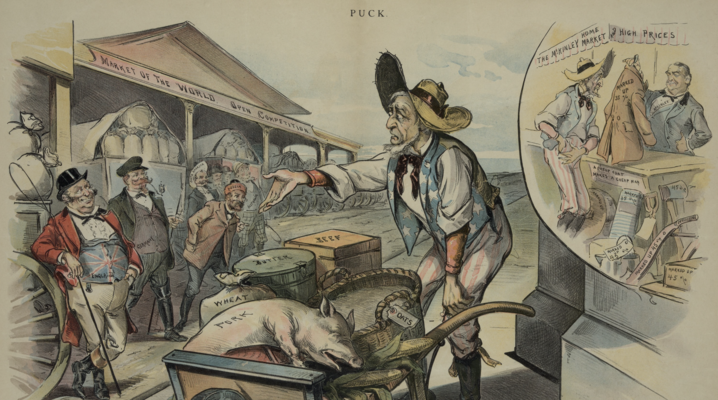

Nevertheless, Roosevelt appeared in an iconic Puck political cartoon titled “The Tariff Tots,” which featured the president, with a piece of paper bearing the words “Tariff Revision,” peering menacingly at a group of giant-sized children playing in front of a “Home for Infant Industries.” In the background, a nurse named “Dingley Tariff” supervises the children, whose school book reveals, “D is for Dingley whose name we revere.” The idea was that these “infant industries” couldn’t survive without the government’s protection. Roosevelt was faced with a question: “Oh, Sir, you would not turn these helpless, half-grown babes out into a cruel world, would you?”

If Roosevelt’s successor had been asked the same question, he wouldn’t have hesitated. For William Howard Taft, a self-titled tariff revisionist, lowering tariffs was a top priority. He warned that the “danger of excessive rates was in the temptation they created to form monopolies in the protected articles, and thus to take advantage of the excessive rates by increasing the prices . . . .”

Taft, like Cleveland, appeared bedeviled by opponents; the Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act, which the president signed, only moderately decreased rates and frustrated Taft’s progressive supporters. His most enduring contribution to the debate over tariffs was his push for a constitutional amendment allowing the federal government to collect an income tax, helping to offset the loss of tariff revenue. “[An income tax] might be indispensable to the nation’s life in great crises,” he remarked. Congress agreed. Over the next three years — even as Taft and Roosevelt became bitter rivals, running against each other in the 1912 presidential election, splitting the vote, and paving the way for Woodrow Wilson’s victory — states worked to ratify the proposed amendment. On February 3, just one month before Wilson’s inauguration, the Sixteenth Amendment was officially adopted.

Revenue from the income tax gradually replaced tariff revenue as the federal government’s primary source of income. However, between Herbert Hoover’s disastrous Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, John F. Kennedy’s calling for the “mutual lowering of tariff barriers among friendly nations so that all may benefit from a free flow of goods,” and Ronald Reagan’s denouncing tariffs in 1987, they have continued to play an integral role in presidential history. Indeed, 112 years after the passage of the Sixteenth Amendment, the 47th president has proven that the Founding Fathers’ debate about duties is still very much alive and well.

Napoleon and Tariff Tots: How Past Presidents Viewed Tariffs

Published in Blog on April 09, 2025 by Jakob Fay