It’s difficult to sit in the year 2021 and comprehend what it meant for the Patriots of the Revolution to take a stand against the greatest and most powerful Empire in the world - and fight for an idea that had never been fully fleshed out in society. Self-governance? Individual liberty? God-given rights?

Sure, our framers had borrowed heavily from political philosophers like John Locke - but this American experiment was new and unknown and nothing more than a pipe dream when men and women stood in solidarity and fought for it.

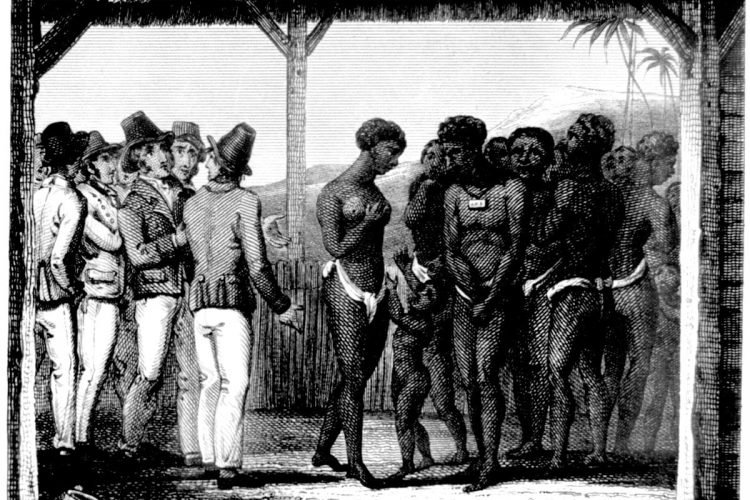

And what of the enslaved men who fought for this nation? A nation that took nearly 89 years after the Declaration of Independence to fully abolish slavery? It is estimated that between 5-8,000 slaves fought beside the Patriots for freedom (approximately 20,000 for the Crown), for a promise that would take much much too long to be granted to every citizen of this nation.

Jeffrey Brace, unlike most of the Patriots discussed, did not have a family or pedigree. He was not politically connected, nor did he seek a position of power or prestige following the Revolution. Jeffrey Brace, nee Boyrereau Brinch, was an African-born slave who spent his youth and young adulthood facing the horrors of slavery as he was brought through the Carribean and Middle Passage, to Barbados, where he would eventually be purchased and brought to America.

Brace’s story was captured by a lawyer named Benjamin Prentiss and published by Harry Whitney in 1810. The Blind African Slave, Or, Memoirs of Boyrereau Brinch, Nicknamed Jeffrey Brace is one of the rarest published accounts of enlistment and service in the Revolutionary War.

Prentiss, an advocate of the abolishment of slavery, wrote:

“In America that spirit of liberty, which stimulated us to shake off a foreign yoke and become and independent nation, has caused the New-England states to emancipate their slaves, and there is but one blot to tarnish the lustre of the American name, which is permitting slavery under a constitution, which declares that ‘all mankind are naturally and of right ought to be free.’ Whoever wishes to preserve the constitution of our general government, to keep sacred the enviable and inestimable principles, by which we are governed, and to enjoy the natural liberty of man, must embark in the great work of exterminating slavery and promoting general emancipation.”

Prentiss connected with Brace, who was 70 at the time, to write The Blind African Slave and tell of Brace’s life story, his commitment and dedication to the Revolutionary war, and the principles of freedom outlined in the Constitution. This writing was used to challenge Americans to live up to the ideals of the Revolution, emancipating slaves, and truly establishing a country of free citizens.

Brace was born Boyrereau Brinch in 1742 in the Niger River Basin in what is now southern Mali. He was captured when he was 16 by slave traders and faced the inhuman brutality of chains, tourture, starvation, and death of those around him as he was brought to Barbados. The book describes in clear detail the horrors of slavery, bringing to light the reality of what it meant to be enslaved - a shocking and monumental read, particularly for the year 1810.

Brace was brought to America after being purchased by a New England merchant privateer, Isaac Mills, and was forced to fight in the French and Indian War. He was injured during a fight with a Spanish ship when he was shot through the hip and ankle, an injury that would stay with him for the rest of his life.

Following the war, Brace was sold and purchased a number of times - moving through New England while facing continuing brutality of being owned by sadistic men. His story of survival was at odds with the regularly accepted idea that slavery in New England was “kinder and gentler” compared to the South, and outlined the horrors he faced.

Brace’s life continued in turmoil until he was sold to Mary Stiles, a widow. Stiles taught Brace to read and speak clearer English and he was taught to read the Bible. Stiles died in 1774 and Brace became property of her son, Benjamin. Though the book does not mention any of the lead-up to the Revolutionary War, Brace enlisted in the Army, stating:

"[I have] entered the banners of freedom. Alas! Poor African Slave, to liberate freemen, my tyrants.”

Though not clearly documented, it is most likely that Brace was a manumit for Benjamin Stiles, perhaps a stand-in for Stiles’s middle son. Many Connecticut slave masters would manumit their slaves in exchange for their military wages - permitting the enslaved to purchase freedom.

Others would permit freedom for those slaves who fought in the Revolution, and some emancipated their slaves outright as they felt slavery was incongruent with what the Patriots were fighting for. It is not clear what the agreement with Benjamin Stiles was, but Brace enlisted in 1777 at the age of 35.

Brace was involved in a number of skirmishes, including the Battle of Ridgefield, and quickly demonstrated his skill as a soldier. He was assigned to the Sixth Regiment’s light infantry company - a highly skilled group of soldiers who wore distinctive leather helmets that Brace called “leather caps.”

He remained in light infantry for the remainder of the war, fighting bravely in many battles. He served in the Continental Army for more than five years, and was discharged in 1783 having been awarded the Badge of Merit - a distinction from George Washington to honor those who were most loyal.

Brace returned to the home of Benjamin Stiles for a year following his discharge, a free man. He moved around freely, purchasing and selling land and property, got married and had a family, though he continued to face discrimination in New England. Brace ultimately settled in Georgia with his family in his late 60s, meeting Benjamin Prentiss during that time.

The recording of Brace’s story is a phenomenal look into the birth of our Nation through the eyes of a man who joined forces with those who did not view him as equal. Brace’s hope is obvious through his retelling, as was his allegiance to freedom - an ideal “all mankind have equal right to possess.”