“Publius” is remembered to this day for writing arguably the greatest primer on the U.S. Constitution in American history, “The Federalist Papers.” Amazingly, in its final essay, the legendary work of political genius made a compelling case for an Article V amendatory convention.

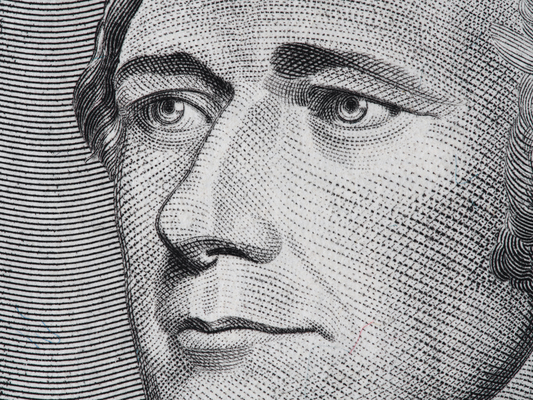

Following the Constitutional Convention in 1787, the three-person writing team of James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay embarked on the momentous errand of persuading the American people (specifically New Yorkers) to support the new government charter.

They were opposed in their efforts by the “anti-Federalists,” who argued that the Constitution would make the national government too powerful thereby eroding individual liberties. As it would take the ratification of at least nine states to put the document into effect, it was the job of the Federalists to prove their opponents wrong; to prove that the new Constitution would give government just enough power to do what it could not under the impotent Articles of Confederation, while still safeguarding the fundamental principles of self-governance.

In the final Federalist Paper, Federalist No. 85, Hamilton tackled the question of the “security which [the Constitution's] adoption will afford to republican government, to liberty, and to property.” He noted, however, that, after 84 prior papers, the question had already been adequately answered.

“Let us now pause,” he wrote, “and ask ourselves whether, in the course of these papers, the proposed Constitution has not been satisfactorily vindicated from the aspersions thrown upon it; and whether it has not been shown to be worthy of the public approbation, and necessary to the public safety and prosperity.”

Hamilton reminded his readers that the “very existence of the nation” hinged upon what they decided about the adoption of the Constitution. He urged them to “sincerely and honestly” consider the arguments he and his colleagues had laid out. In fact, he said they had a duty to do so.

For his part, Hamilton felt “an entire confidence” in the veracity of their reasoning. Nevertheless, he spent his closing remarks making one final push for adoption.

Interestingly, in his attempt to assuage the fears of the skeptic, Hamilton raised the subject of an Article V Convention. Addressing the argument that the Constitution – which he called “the best that the present views and circumstances of the country will permit” – should be made perfect before adoption, Hamilton posited that amending the Constitution post-adoption seemed preferable.

He then tackled the counter-argument that “persons delegated to the administration of the national government will always be disinclined to yield up any portion of the authority of which they were once possessed.” In other words, – in the more modern language of Ronald Reagan – “No government ever voluntarily reduces itself in size.”

Of course, this is true. But in light of Article V, Hamilton argued that “the observation is futile.”

“[T]he national rulers… will have no option upon the subject,” he stated. “By the fifth article of the plan, the Congress will be obliged ‘on the application of the legislatures of two thirds of the States… to call a convention for proposing amendments, which shall be valid, to all intents and purposes, as part of the Constitution, when ratified by the legislatures of three fourths of the States, or by conventions in three fourths thereof.’ The words of this article,” he continued, “are peremptory. The Congress ‘shall call a convention.’ Nothing in this particular is left to the discretion of that body. And of consequence, all the declamation about the disinclination to a change vanishes in air.” [emphasis added]

He then added, “We may safely rely on the disposition of the State legislatures to erect barriers against the encroachments of the national authority.”

The parallel between Hamilton’s language about an Article V Convention and contemporary advocates’ language is astonishing. Translate Hamilton’s words into more modern, accessible English, and it sounds almost identical.

We also see that he took for granted that the states would utilize Article V. “We may safely rely on the disposition of the State legislatures to erect barriers against the encroachments of the national authority,” he wrote. In his mind, there was no question that we would employ that powerful tool. Accordingly, we can imagine his shock upon discovering that, even in this age of unprecedented national encroachment, there are still so-called “constitutionalists” standing in the way of using Article V.

In his closing argument on why the states should adopt the U.S. Constitution (and trust that their liberties and rights would be secure), Hamilton chose to highlight Article V. The proposed document might not have been perfect, he acknowledged. But for as long as the American people had and used Article V, he was confident the federal government would not get out of hand.

To join us in making Hamilton's vision a reality, sign the Convention of States petition below.

What Federalist No. 85 says about Convention of States

Published in Blog on March 22, 2023 by Jakob Fay