Sixty years ago today, on August 28th, 1963, hundreds of thousands of peaceful protestors, sick of racism, mistreatment, and inequality, joined together in the historic March on Washington. Their demands were straightforward; their purpose was clear; their cause “a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.”

The pinnacle of the day was the glorious moment in which Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his immortal “I Have a Dream” speech from the majestic steps of the Lincoln Memorial. He dreamt of an America in which his children would “not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” He dreamt of “an oasis of freedom and justice.” And 60 years later, it seems as if we have come closer to reaching that dream than ever before.

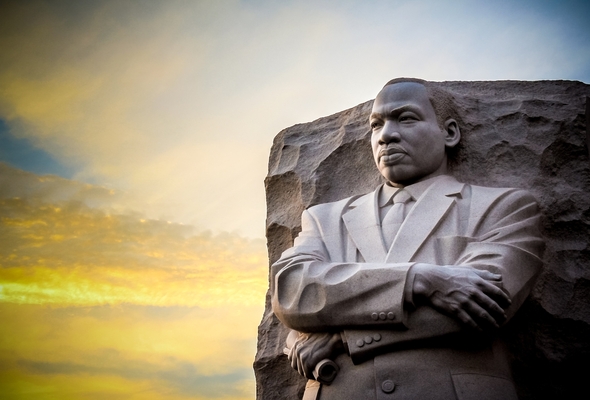

Today, MLK is widely recognized as one of the most important figures in American history. He’s a hero to millions. The more we study his life, work, and speeches, the more we’ve come to appreciate his contributions to American society.

Considering his continued popularity amongst both Republicans and Democrats and his huge influence on modern political thought, though, it’s hardly surprising—but no less regrettable—that the legend has been turned into a political weapon, wielded relentlessly by rival partisans.

In recent years, the right and left alike have overused King’s words to justify completely opposing political views, particularly concerning issues of racial justice, and in so doing, have lessened his most revolutionary ideas to mere platitudes. That a single, misconstrued MLK speech can be used both to vindicate and castigate a BLM riot or protest, for example, seems to suggest that either one side misunderstands MLK completely or both have missed the mark slightly.

But today, as we honor King, I don’t want to celebrate him for the purpose of scoring political points against opponents but for the purpose of understanding the magnitude of his accomplishments in the context of his time and the wider context of American history as a whole. How and why did he become a hero to all Americans?

The real reason is that he advanced our society in a way that few other Americans ever have.

Preceding the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 60s, black Americans were excluded from equal participation in society and grossly mistreated. There is no question that this pervasive discrimination is one way in which America fell far short of her noble aspirations for liberty and justice for all. Our American Creed, outlined in the Declaration of Independence, was meant for all Americans, but, in practice, it routinely fell short of actually applying to all Americans.

MLK addressed this shortcoming in his “I Have A Dream” speech and demanded a change:

“When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men—yes, black men as well as white men—would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked insufficient funds.

And so we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice."

As he acknowledged in the above quotation, King made an appeal to America’s founding principles. He did not seek to rewrite them. He built on the imperfect foundation that previous generations of Americans had established. He did not seek to destroy it. His efforts were simply a fulfillment of—not a contradiction to—America’s founding.

To better interpret this important facet of King’s philosophy, we must turn to his predecessor, Frederick Douglass, who, just as MLK would do decades later, drew upon the past to better the future.

Specifically, we must examine his controversial “Hypocrisy of American Slavery” speech.

The very title of Douglass’ 1852 Independence Day address says a lot about his views on America: the word “hypocrisy” suggests that Douglass is making a contrast—a contrast between who America was ordained, by God and her Founders, to be and who she had become in practice. Slavery was not in alignment with America’s founding; it was in direct contradiction. Hence, the hypocrisy.

Make no mistake, the famous abolitionist was disgusted at his country and clearly no fan of the Fourth. To in any way whitewash his harsh words of rebuke would be unfair to history. In the 1850s, America was not undeserving of Douglass’ reproval.

“I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary,” the former slave proclaimed. “Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you this day rejoice are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity, and independence bequeathed by your fathers is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth of July is yours, not mine,” he mourned.

“What to the American slave is your Fourth of July? I answer, a day that reveals to him more than all other days of the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mock; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade and solemnity, are to him mere bombast."

Whatever they expected to hear upon inviting him to deliver Independence Day remarks, one can imagine his hearers’ discomfort. Douglas held nothing back. On a day of celebration, he chose to bewail and berate. And for good reason.

Yet threaded throughout his speech is a narrative, found also in King’s 1963 Dream, that present-day anti-Americanism has acutely abandoned: an appeal to our founding.

The orator evokes “the name of the Constitution and the Bible.” “Would you have me argue that man is entitled to liberty,” he asks. “That he is the rightful owner of his own body? You have already declared it,” he states, referring to the nation’s founding documents. “The feeling of the nation must be quickened; the conscience of the nation must be roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed [emphasis added]; and its crimes against God and man must be denounced,” he urged.

Douglass had no quarrel with America’s foundational creed that all men are created equal and are endowed, by their Creator, with certain unalienable rights including life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. He had no reason to destroy America. No reason to destroy what she stood for. He had the intellectual honesty to admit that America, as an idea, was a beautiful concept. His mission was to help the rest of the nation realize the potential inherent in its founding. In a sense, it was to make America (in reality) more like America (in theory).

If America were truly founded on slavery—as we are told today she was—American slavery would not be hypocritical. It would be no less reprehensible, but not necessarily hypocritical. Douglass aimed to show his countrymen how grossly they had fallen short, yet he never argued that the nation itself was fundamentally evil. Born in self-governance, America had somehow denied self-governance to entire subsets of its populace, but its noble promise was still there… if only Douglass’ generation would reclaim it.

As unsettling as his speech may be (both in 1850 and 2023), his words were no doubt necessary. America had not yet lived up to her full potential, but thanks, in part, to Fredrick Douglass and his no-holds-barred discourse, we were on our way to becoming a more perfect union. And over a century later, MLK would walk the nation another step—nay, leaps and bounds—closer to that illustrious end goal.

Through protests, legislation, important speeches, and social changes stemming from the family, MLK shifted American culture away from its racist smears and atmosphere, bringing us nearer to fully obtaining the Founder’s worthy vision for the country. By ensuring that unalienable rights—endowed upon us by our Creator and recognized in the Declaration of Independence—were applied fairly to all Americans, regardless of race or ethnicity or political affiliation, he steered the nation in the direction of ultimately realizing the self-evident truths the Republic had been built on.

Fans of King should love America’s Founding, just as King himself did. Fans of America’s Founding should love King for he advanced it, fulfilled it. He’s a hero not for Republicans or Democrats but for Americans. The Reverend and his 1963 address to the nation remind us, just as Douglass before him did, that America never has been a perfect nation, but, thanks to luminaries like Martin Luther King, we can continue to form her into a more perfect union.