Oregon supporter Andrew Shooks recently penned an excellent op-ed on reclaiming self-governance. One phrase, in particular, captured my attention:

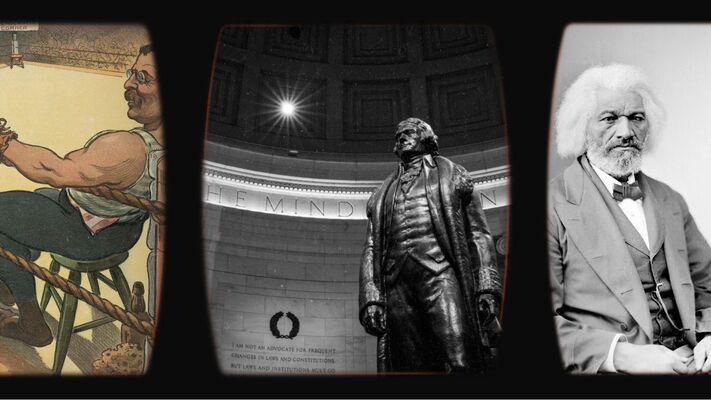

“Reclaiming self-governance is not a one-time act,” he wrote, “it's a lifelong commitment. It's about rediscovering the spirit of Jefferson, the audacity of Douglass, the resilience of Roosevelt. It's about remembering that America is not a spectator sport, it's a participatory republic.”

The spirit of Jefferson… the audacity of Douglass… the resilience of Roosevelt.

We, unfortunately, live in an age of shallow political thinking. Our “reasoning” — if it even deserves to be called that — is reduced to cursory, emotional, “gotcha”-based baiting. While good writers and thinkers take the time to craft powerful and compelling ideas — ideas that necessitate more than a short tweet to convey — “X,” formerly known as Twitter, sucks the substance out of our public discourse and leaves us, instead, feeling shocked, outraged, and ultimately, uninformed.

But I digress. My point is twofold: Firstly, Andrew Shooks’ claim about Jefferson, Douglass, and Roosevelt is not that kind of statement. It requires deeper thinking than is typically demanded of today’s headlines-only audience. Why Jefferson? Why Douglass? Why Roosevelt? Why not, say, Hamilton, Lincoln, and Armstrong? What correlates those three men with the adjectives that precede their names?

Secondly, Jefferson, Douglass, and Roosevelt each made an enduring impact not because they knew how to shock audiences with their subversive but superficial hot takes, but because they knew how to think well. Today, we often confuse prominence for progress. We wrongly assume that because someone is causing a ruckus, riling up the social media mob, they are “making a difference.” They are not — at least not inherently. Fredrick Douglass, the famed abolitionist orator and author, in particular, perfected the art of shocking an audience, making his hearers squirm uncomfortably in their seats. But his was not a purely shock-based performance. His rhetoric, intentionally goading at times, was, beyond that, deeply rooted in reason and truth. More than sucker punching a crowd, which he, with his words, was more than capable of doing, he knew he needed to give them something to chew on. Similarly, Thomas Jefferson, as we will see, heartily promoted rebellion — a spirit of rebellion. But an important distinction must be made. Jefferson did not advocate for the spirit of borderline anarchy that hangs over many who claim his spirit of rebellion today. His words, so easily misconstrued, were, like Douglass’s, embedded profoundly in thought.

With that in mind, turn again now to each of Shooks’ idioms:

“The spirit of Jefferson” — To most students of history, this phrase probably recalls Thomas Jefferson’s 1787 letter to Abigail Adams, in which he declared, “The spirit of resistance to government is so valuable on certain occasions, that I wish it to be always kept alive. It will often be exercised when wrong, but better so than not to be exercised at all. I like a little rebellion now and then.”

These are powerful words from the author of the Declaration of Independence. But we must not forget his critical warning: “Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed.” Notably, he then laid out a “long train of abuses and usurpations” that not only justified but obligated the colonists to rebel against Great Britain.

Thomas Jefferson, in other words, was all for resistance. But he also recognized the all-important need for thoughtful wisdom. The spirit of Jefferson, therefore, was one of resistance and prudence.

Ironically, perhaps the best commentary on the topic comes from the Abigail Adams letter to which Jefferson was responding: “Instead of that laudible Spirit which you approve, which makes a people watchfull over their Liberties and alert in the defence of them,” she wrote, “these Mobish insurgents are for sapping the foundation, and distroying the whole fabrick at once.”

Mrs. Adams’ insight was prescient: Yes, we must be watchful. Yes, we must be alert. But we also must guard against a certain mobbish spirit of insurgency which, in the name of defending liberty, inadvertently undermines the whole foundation.

That is what the spirit of Jefferson teaches us.

“The audacity of Douglass” reiterates a similar lesson. From his youth on the docks in Baltimore, Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was a scrappy man. His mastery of the English language gave a voice to his merited outrage, directed not only at American chattel slavery, into which he was born, but also at the pious, white-washed Southern hypocrites and racist Northern appeasers who enabled that dehumanizing system to persist. Douglass’s standard routine was designed to disturb both groups.

Indeed, he spoke with audacity. Likely no other man in history could have gotten away with reproving Abraham Lincoln at the dedication of the Emancipation Memorial in memory of the late president. (“Mr. Lincoln shared the prejudices of his white fellow-countrymen against the Negro,” he said, among other unfavorable judgments.) But that’s just what Douglass did — he spoke truth to power, and he did so fearlessly. Audaciously.

But before we count Douglass among those curmudgeonly trolls who wrangle without end in the comments section, we must remember that he always spoke with purpose. His calling was higher than simply raising ire for the sake of raising ire. He knew how to exploit his childhood slavery story for maximum emotional impact, but he was not click-baity. He aimed to make a radical change, to eradicate a repugnant evil. And that is exactly what he did. The spirit of Douglass, therefore, was one of audacity and purpose.

Lastly, perhaps no American can better teach us resilience than Theodore Roosevelt, the man in the arena. Once a “sickly, delicate boy,” the 26th president of the United States famously embraced the strenuous life and was admired for his vigor and larger-than-life persona. From scrawny to robust, Teddy was indeed resilient.

But, like Jefferson and Douglass before him, he exemplified this signature strength in pursuit of a higher calling than mere selfish gain — what he in his “Man in the Arena” address deemed a “worthy cause.” For Roosevelt, that worthy call was “Americanism,” which meant “the virtues of courage, honor, justice, truth, sincerity, and hardihood — the virtues that made America.” History remembers Theodore Roosevelt not merely because he was a stalwart man, but because he employed his most celebrated virtues in service of a greater good. The spirit of Roosevelt, therefore, was one of resilience and service.

Today, our “worthy cause” is, as Andrew Shooks properly identified, reclaiming self-governance. But, as these giants of history teach us, it takes more than blind insurgency, emotionality, and useless showmanship to save the Republic. It takes resistance with prudence, audacity with purpose, resilience with service.

The spirit of Jefferson, the audacity of Douglass, the resilience of Roosevelt

Published in Blog on March 05, 2024 by Jakob Fay