The Federalist Papers were a series of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay in 1787 and 1788 to support the ratification of the U.S. Constitution.

They are widely viewed as the most authoritative source of information to understand the system of government envisioned by the Founders who participated in the Constitutional Convention of 1787 that created the Constitution to address the defects of the previous Articles of Confederation.

This post is the first of a series discussing the concepts addressed in The Federalist Papers related to Article V, federalism, and issues that are proposing to be addressed through an Article V convention.

In this first installment, we will begin by addressing whether or not the authors of The Federalist Papers felt that the concept of Article V convention was even worth mentioning and, if so, what level of importance was placed on this method of amending the Constitution.

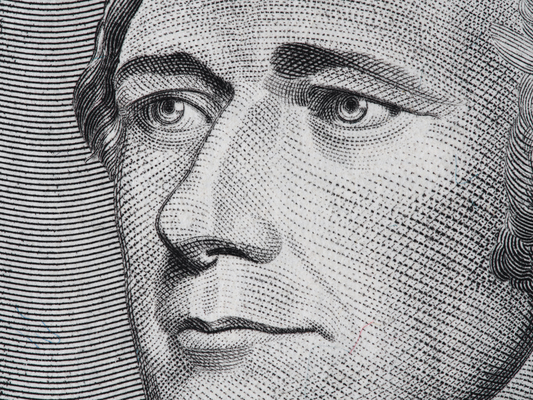

Ironically, the answer to this question is contained in the very final essay of The Federalist Papers (#85), written by Alexander Hamilton and published in August 1788.

In his essay, Mr. Hamilton forthrightly admits that although he supports the ratification of the Constitution, he does not consider it an ideal system of government by any means and that he can see some merit in the arguments in the opponents of ratification:

“I shall not dissemble that I feel an entire confidence in the arguments which recommend the proposed system to your adoption, and that I am unable to discern any real force in those by which it has been opposed. I am persuaded that it is the best which our political situation, habits, and opinions will admit, and superior to any the revolution has produced.”

After this admission, however, Mr. Hamilton rejects the idea that the proposed Constitution is “radically defective” and proceeds to explain how the amendment process in the Constitution can address any deficiencies that exist:

“In opposition to the probability of subsequent amendments, it has been urged that the persons delegated to the administration of the national government will always be disinclined to yield up any portion of the authority of which they were once possessed. For my own part I acknowledge a thorough conviction that any amendments which may, upon mature consideration, be thought useful, will be applicable to the organization of the government, not to the mass of its powers; and on this account alone, I think there is no weight in the observation just stated. I also think there is little weight in it on another account. The intrinsic difficulty of governing thirteen States at any rate, independent of calculations upon an ordinary degree of public spirit and integrity, will, in my opinion constantly impose on the national rulers the necessity of a spirit of accommodation to the reasonable expectations of their constituents.”

It is clear from this passage that Mr. Hamilton strongly believed that the federal government as an entity would not serve as a significant impediment to necessary reforms via the amendment process that reduce their power and authority (a view that unfortunately has been disproven by subsequent history).

However, he then specifically cites an Article V convention as the means to prevent the Federal government from engaging in this type of obstructionist behavior:

“But there is yet a further consideration, which proves beyond the possibility of a doubt, that the observation is futile. It is this that the national rulers, whenever nine States concur, will have no option upon the subject. By the fifth article of the plan, the Congress will be obliged 'on the application of the legislatures of two thirds of the States which at present amount to nine, to call a convention for proposing amendments, which shall be valid, to all intents and purposes, as part of the Constitution, when ratified by the legislatures of three fourths of the States, or by conventions in three fourths thereof.' The words of this article are peremptory. The Congress 'shall call a convention.' Nothing in this particular is left to the discretion of that body. And of consequence, all the declamation about the disinclination to a change vanishes in air.”

The language Mr. Hamilton uses in this passage could not be clearer regarding the validity of an Article V convention and the inability of Congress to prevent such a convention once it has been duly called by two-thirds of the states.

Therefore, it is beyond question that the Founders, through the views expressed in The Federalist Papers, not only intended for an Article V convention to be a valid method of proposing constitutional amendments, but also saw this as the ultimate bulwark against the usurpation of power by the federal government that rightfully belongs to the states and the people.