On March 4, 1865, Abraham Lincoln laid out his agenda — “With malice toward none, with charity for all….” Thusly, said the president, the war would end.

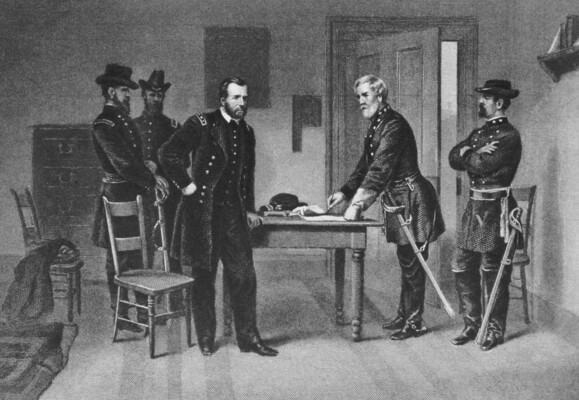

One painfully prolonged month later, on April 9, Lincoln’s commanding general, Ulysses S. Grant, implemented the commander in chief’s benevolent plan for national peace and rehabilitation. A stately home in Virginia, Appomattox Court House, would play host to the historic occasion.

The dignified but defeated Robert E. Lee, immaculately dressed, knew that surrender meant more than just admission of defeat; it meant admission of treason. Having taken up arms against the Union, the commander of the Confederate States Army and his band of rebels were liable to be punished accordingly. Lee had dodged the inevitable for weeks now, but no longer — the Confederacy was finished.

His army, fate, and future lay in Grant’s hands.

Much has since been said about the Union hero’s slovenly appearance on this occasion of inestimable importance. Grant himself, one historian writes, “was painfully aware of how poorly costumed he was to enact this lofty scene…. Later asked what was uppermost in his mind at this sublime moment, a sheepish Grant said prosaically: ‘My dirty boots and wearing no sword.’”

Nevertheless, despite the gaping discrepancy in appearance, one man clearly had emerged victorious over the other, the former “sitting his saddle with the ease of a born master, taking no notice of anything, all his faculties gathered into intense thought and mighty calm. He seemed greater than I had ever seen him,” a veteran of Gettysburg marveled, “a look as of another world about him. No wonder I forgot altogether to salute him. Anything like that would have been too little.” An old suit and mud-caked boots notwithstanding, Grant played the part well; his presence commanded respect.

SEE ALSO: Top Presidents Ranked - Indomitable in Purpose

But Grant was not one to gloat. “Magnanimous,” the New York Times later called him, an adjective he earned at Appomattox. For it was here, in his moment of peak triumph and glory, that Grant chose mercy over punishment, healing over retribution. Reconstruction would not be an easy path for the nation to tread, but by rebuffing malice, as his president had envisioned, the general paved the way for a tolerable first step.

“I,” confessed Grant, “felt like anything rather than rejoicing at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse.”

Lee deserved no defense, Grant maintained; but pity — now that was a different matter. An estimated 258,000 of Grant’s Confederate countrymen — they were countrymen now — had been killed; he would mourn alongside them and punish them no more than was necessary.

And what were the terms of this unusual surrender? The Confederates were granted immunity from charges of treason on the condition that they never take up arms against the Union again. Amazingly, if they agreed, they would be “allowed to return to their homes not to be disturbed by United States Authority….” Additionally, soldiers were permitted to keep their sidearms and horses (Grant knew many would need them for farming) while Grant also spared Lee his sword.

“It is more than I expected,” Lee admitted, “hugely relieved.”

SEE ALSO: Q1 in Review — The Grassroots in Action

But Grant's benevolence did not end there. When the vanquishing general learned that his men planned to vaunt Lee’s surrender with a celebratory 100-gun salute, he “at once sent word… to have it stopped. The Confederates were now our prisoners,” he said, “and we did not want to exult over their downfall.” Upon finalizing their terms of surrender, he agreed to feed Lee’s starved men.

“Were such terms ever before given by a conqueror to a defeated foe?” wondered a member of Grant’s staff in awe.

In the years that followed, the commanding general refused to brag about the events of that day. By the end of the day, he could be found proposing a “game of brag (a card game)” with Confederate General James Longstreet. Longstreet later told a reporter that Grant’s “whole greeting and conduct toward us was as though nothing had ever happened to mar our pleasant relations.”

“Why do men fight who were born to be brothers?” he famously inquired.

With malice toward none, indeed. Ulysses S. Grant made the first palliating move toward reunification and earned the admiration of his conquered foe because of it. As evidenced by the former Confederates who served as pallbearers at his funeral and the dozens more who attended the funeral procession, Grant’s post-war name became synonymous with goodwill, generosity, and forgiveness. While it is unfortunate that such healing virtues did not pervade the entirety of the Reconstruction Era, for one brief moment, on April 9, 1865, charity for all truly did seem possible.

And now where are we, 159 Aprils later? Facing down the threat of a second civil war, neither side willing to extend Grant-like forgiveness. Both blind to the sublime truth that Lincoln and his favorite general held so dear: that it is better to live in peace with one’s countrymen than to punish the defeated at risk of disunity. Grant deliberately eschewed the expected merriments of victory in order not to shame his enemy. Could we do the same today? Of course not. Today, shaming the enemy is often the entire point.

But not so for Grant. Not so for Lincoln. “With malice toward none” necessitated that these two giants of history let go of their pride and deny their due self-glory. These are the lessons of Appomattox, still pertinent 16 decades later. These are the traits that planted the seeds of reunification and healing, and they may do so again today.

Appomattox at 159 — What the end of the Civil War can teach us today

Published in Blog on April 09, 2024 by Jakob Fay